Review of Neural Programmers

This post is a work in progress

At ICLR 2016 there were a couple of papers on neural programmers. The architecture of these networks introduce with it many benefits. They have complex operations and have combinations of these operations while being able to successfully generalize over unknown input ranges. Both of these networks outperform sequence to sequence models in many tasks, particularly because of their ability to generalize well.

The first, the Neural Programmer (Neelakantan, et al., 2015)1, is one approach to this. The other, the Neural Programmer-Interpreter (Reed & de Freitas, 2015)2, which won best paper at ICLR 2016, can accomplish a number of very interesting tasks, but requires supervision in the form of correct programs.

Neural Programmer

The Neural Programmer, a neural network augmented with a small set of basic arithmetic and logic operations that can be trained end-to-end using backpropagation. Neural Programmer can call these augmented operations over several steps, thereby inducing compositional programs that are more complex than the built-in operations. The model learns from a weak supervision signal which is the result of execution of the correct program, hence it does not require expensive annotation of the correct program itself. The decisions of what operations to call, and what data segments to apply to are inferred by Neural Programmer.

The Neural Programmer was tested on answering questions from tables, a task which has not previously been tested by neural networks. It contains four modules:

- A question RNN that processes the input question

- A selector that assigns two probability distributions at every time step, over the set of operations and data segments

- A list of operations that the model can apply

- A history RNN that remembers the previous operations and data segments selected by the model until the current time step

Question Module

The question module converts the question tokens into a distributed representation. The last hidden state of the RNN is used as the question representation. For longer questions they use a bidirectional RNN to remember the beginnings of the question better. The hidden states in this case are concatenated from the two ends for the representation.

Selector

The selector produces two probability distributions at every time step: one probability distribution over the set of operations and another probability distribution over the set of columns. Operation selection is performed with a softmax over the matrix storing the representations of the operations and parameter matrix of the operation selector that produces the probability distributions. Data selection is performed with a softmax over the matrix storing the representations of the column names and the parameter matrix of the column selector that produces the probability distribution.

Operations

The model supports two types of outputs:

- scalar output (Ex: Sum of elements in column C)

- list of items (i.e. table lookup) (Ex: Print elements in column A that are greater than 50.)

The outputs have access to the outputs of the model at every timestep enabling it to build powerful compositional programs.

History

The history RNN module keeps track of the previous operations and data segments the selector module chose by encoding the information into the hidden vector of the module at time step t. The previous actions selected by the model are used to induce the probability distributions over the operations and columns.

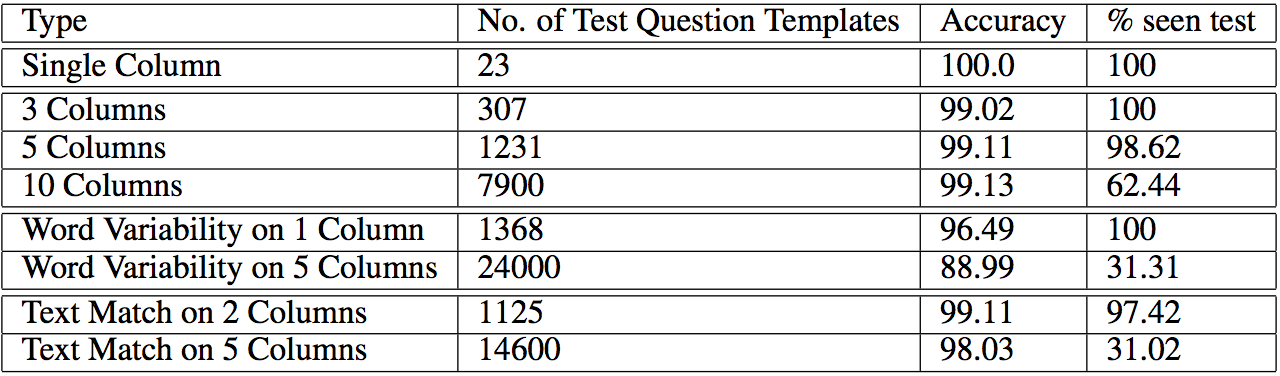

Experiment

50,000 question, data source and answer triples were used as synthetic examples to train the network. Expensive annotations are not required for the training examples and Neural Programmer doesn’t need rules to guide the program other than the given triple, making it a general framework. As a result, they claim that one only needs to define basic operations which requires human effort than previous induction techniques. The model performs very well and can generalize to unseen question templates.

Neural Programmer-Interpreter

The neural programmer-interpreter (NPI) — a recurrent and compositional neural network that learns to represent and execute programs. NPI has three learnable components: a task-agnostic recurrent core, a persistent key-value program memory, and domain-specific encoders that enable a single NPI to operate in multiple perceptually diverse environments with distinct affordances.

The network is trained on fully-supervised execution traces where “each program has example sequences of calls to the immediate subprograms conditioned on the input”. They claim that because these examples are so rich, the NPI can learn from, rather than training on a large number of weaker labels.

One feature of the NPI is that can learn new programs. Traditional neural network agents have difficulties with this because training on new tasks causes performance to suffer on old tasks. In NPI, the core module’s (which is an LSTM) weights are fixed. Rather, updates are made to program memory, where different programs correspond to program embeddings.

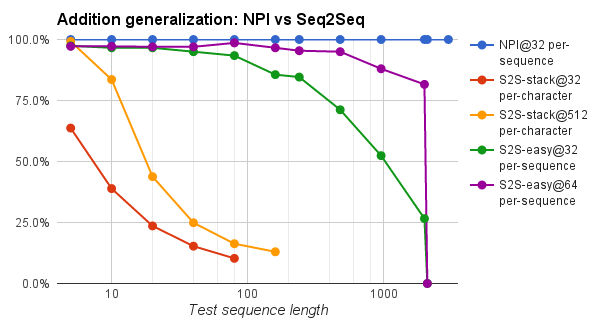

In one experiment, to evaluate generalization ability, a comparison between NPI and sequence-to-sequence models was demonstrated with the addition task. The NPI was “trained on 32 examples for problem lengths 1,…,20 generalizes with 100% accuracy to all the lengths [they] tried (up to 3000)”. The Sequence-to-sequence model (S2S-stack) was trained on twice as many examples with length over 2000, yet barely generalizes for length over five.

This is because NPI learns how to perform programs well using local information such as adding single digits or performing carries. They believe that this lack of locality for sequence-to-sequence models has a large impact on its generalization performance.

The Big Picture

Both of these new models have shown superior results on many tasks that previous model architectures couldn’t achieve. Their ability to generalize extremely well and due to fact they understand the underlying operations to solve problems. It will be exciting to see the developments in these models that generate programs. Unfortunately, there are currently no complete open source implementations of either of these works.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.08228

Footnotes/References

-

Neelakantan, A., Le, Q. V., & Sutskever, I. (2015). Neural programmer: Inducing latent programs with gradient descent. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.04834. ↩

-

Reed, S., & de Freitas, N. (2015). Neural programmer-interpreters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.06279. ↩